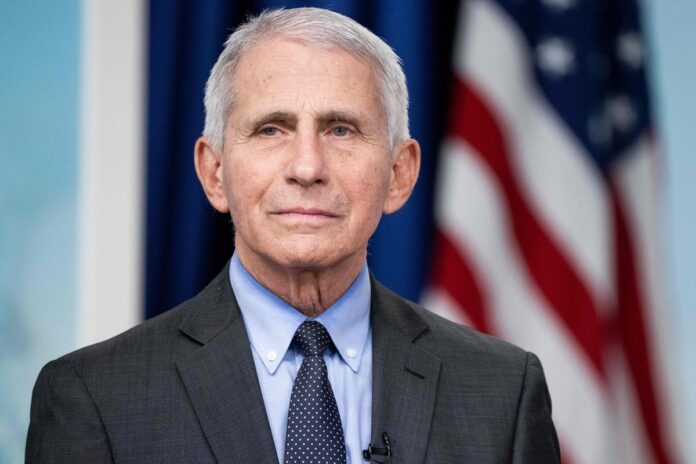

Anthony Fauci became a household name during the COVID pandemic. But the genially stubborn infectious disease doctor, who spent decades helming one the U.S. government’s most important medical research institutes, had made his mark well before that.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, N.Y., as the grandson of Italian immigrants, Fauci became a physician who would go on to spend almost 40 years as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health. He was a member of the White House Coronavirus Task Force under President Donald Trump and served as chief medical adviser to President Joe Biden. He has worked under a total of seven U.S. presidents, overseeing the government’s response to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, avian influenza, anthrax attacks, Ebola outbreaks and, of course, COVID.

Fauci, now age 83, chronicles his wide-ranging career in his memoir On Call: A Doctor’s Journey in Public Service, published in June. In it he describes his unwavering commitment to furthering science—regardless of which political party was in power—and to meeting the needs of patients.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

His first big challenge came during the dark early days of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s, when a mysterious new illness began sickening and killing large numbers of people in the U.S.—predominantly gay men, at first. President Ronald Reagan’s administration was slow to take action, provoking anger, anguish and frustration among the gay community and supporters. As head of NIAID, Fauci became the prime target of that ire; some activists went so far as to call him a “murderer.” Taking their criticisms to heart, Fauci met with activists to hear their concerns. He eventually won their trust by including them in policy discussions and expanding access to lifesaving treatment.

After 9/11 he helped lead the government response to the anthrax attacks and the potential threat of biowarfare. He also navigated the international outbreaks of bird flu (a variant of which is currently spreading among cattle and poultry and in farm workers in the U.S.) in the late 1990s and 2000s, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014–2016 and other crises.

In January 2020 Fauci—and soon the rest of the world—confronted a challenge the likes of which hadn’t been seen in at least 100 years: COVID. As part of President Trump’s Coronavirus Task Force, he had a direct role in issuing public health advice to the country. And as head of NIAID, he oversaw development of one of the COVID vaccines. Fauci writes in his memoir that Trump had initially seemed to like him but that the president and his allies quickly turned on Fauci for speaking plainly about the threat COVID posed to the nation. He received death threats and was repeatedly grilled and maligned by right-wing members of Congress over policies around masking and social distancing, as well as the origin of the COVID-causing virus SARS-CoV-2 itself.

Still, Fauci remained outwardly unphased in his mission to protect lives. In late 2020 two safe and highly effective mRNA vaccines (one of them the result of work at the NIH) were unveiled and began to be administered. Estimates suggest COVID vaccines saved more than 14 million lives worldwide in a year.

Fauci retired from NIAID in December 2022. Since July 2023 he has been a distinguished university professor at Georgetown University’s School of Medicine and the McCourt School of Public Policy.

Scientific American spoke with Fauci about his long, distinguished career in medicine and public service, the challenges he faced during multiple epidemics—and the lessons that could help prepare us for the next one.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

The last time I interviewed you was in January, 2020. So a lot has happened since then!

Yeah, I would say I think a lot has happened in the world since then.

What was it like working in the government during the height of COVID, and how did you handle the challenge of communicating the dangers of a totally new virus—when experts’ knowledge was changing day to day?

We were dealing, essentially, with a moving target because [the COVID-causing virus] SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 were truly unprecedented, the likes of which we had not seen for well over a hundred years.

The worst possible case scenario is what actually happened to us, where we had an outbreak that lasted intensively for two and a half years and in duration for well over four years. Communicating with the public became a real problematic issue because unlike with other diseases, our knowledge of—and the actual reality of—the virus evolved over months and years.

For example, in the first few months, from the information we were getting from China, it was felt that this was a virus that was not transmitted efficiently from human to human. But it became clear that the virus was transmitted very efficiently, and about 60 percent of the transmissions were from someone who had no symptoms at all—which was really unprecedented in respiratory illnesses.

And then, as the months and years went by, the big surprise was that the virus kept on changing. We had different variants. It is difficult when the public wants definitive answers that are immutable when you’re dealing with an evolving situation. One lesson learned from this for the next time is that we have to make it very clear when we’re speaking to the public that we are dealing with evolving information. And we’ve got to make it clear that that is because the virus and the outbreak are changing—not because scientists are flip-flopping.

Do you think now, with the benefit of hindsight, there were some things that we could have communicated better early on—for example, the airborne spread of SARS-CoV-2?

As an outbreak that killed 1.2 million Americans, certainly, there were many things that could have been done differently. We were trying our best in the public health arena, and our main goal was to save lives.

The [World Health Organization] took a long time to tell the world that we were dealing with a virus that was spread by aerosols. I mean, we were getting information about aerosol spread in the early months of the outbreak, and it wasn’t until well into the real height of it that the WHO said, Well, okay, yeah, now we know it was aerosol transmission. The virus stays in the air and can float around, and you can get infected when you’re on the other side of the room.

Did that contribute to public backlash? There was this idea that masks didn’t work, and there was a lot of confusion. But once we knew that there were aerosols involved, that shifted the kinds of masks that people needed, right?

Masking is a very complicated issue. There are many, many factors. The idea of pushing back on public health regulations by people who felt that their liberties were encroached upon when people were telling them they had to wear a mask under certain circumstances—I guess that’s understandable. We’re a country of free spirits. But that worked against a unified public health intervention that would have been helpful. Now, when you look back at all the data, there’s no question that mask wearing saved lives.

“It’s like being at war. The common enemy is the virus. And we were acting in many situations and in many respects as if the enemy were each other.” —Anthony Fauci

Of course, masking was one of many things that we could have been doing, including improving indoor air quality through air filtration and ventilation.

Pandemics are almost invariably respiratory-borne because that’s how you get very large numbers of people getting infected. The lesson learned is the importance of paying attention to proper ventilation in classrooms and places of work and installation of HEPA filters in places where there are a lot of people in a closed room. So ventilation needs to be addressed, and it’s not something you can do overnight.

As a society, we’ve got to pay attention to the fact that respiratory illnesses are important even when they don’t result in a full-blown pandemic. That’s the reason why, when you build new structures or when you certify structures, you keep in mind the importance of good ventilation.

We’re currently facing outbreaks of H5N1 avian influenza in dairy cows and poultry in the U.S. and Canada, and there have been several dozen human cases. I know you’ve dealt with avian flu before in a global context. How are we handling the current situation?

Well, you know, we’re at the point where we’re seeing more and more cow herds getting infected and more and more cases arising in people. I’ve dealt with H5N1 going way back to 1997, when it was noted in the very highly pathogenic form in chickens in Hong Kong, and authorities prevented an outbreak by essentially culling all of the chickens in the region. Then, in 2003 and later on, there were more blips in that radar screen of H5N1.

So we’ve had a number of human infections with H5N1, but thank goodness there hasn’t yet been a transmission from human to human. Historically, when H5N1 infected humans, it had a high degree of mortality. It didn’t spread from human to human, but it had a 30 to 40 percent fatality rate, which is horribly high for a respiratory virus. I mean, even the terrible pandemic flu of 1918 only had a 1 to 2 percent mortality rate.

The somewhat encouraging news is that the H5N1 that’s infected humans now has not generally caused serious illness.It predominantly causes a conjunctivitis and mild systemic symptoms. There’s been one case of a person who actually went into intensive care and was hospitalized, but the overwhelming majority did not have serious disease. The sobering news is that that can change because the virus infects more than one species—and we know it can infect pigs.

Pigs are on farms with chickens and with cows. Chickens and cows could infect a pig, and then a human virus can go into the pig. And then you could get a reassortment of a virus that has some of the dangerous qualities of H5N1 and some of the capability of spreading from human to human of a human virus. That could make this something we really have to be concerned about, and that’s the reason why the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] says that although currently the risk in general is low, we still have to pay close attention to the possibility that that might change.

Do you worry that we are not doing enough to contain the outbreak in cows and chickens and other animals?

In the early years of COVID, I said, “We’ve got to flood the system with testing.” My recommendation—and I’m not alone in this; a number of my public health colleagues and my infectious disease colleagues say the same thing—is that we should be doing more widespread serosurveillance testing [testing for antibodies from prior infection]. Maybe a large number of people are asymptomatically infected, and you really need to know that if you’re trying to monitor what the spread of this virus would be.

Do you think that we are any better prepared for a pandemic today than we were four years ago?

Well, I would hope so. I hope that we would learn the lessons of that at the local public health level. You know what? When I evaluate, retrospectively, how we did with COVID, for the sake of clarity, I put it into two separate categories: what the scientific response was and what the public health response was.

I think anyone who looks at the data would agree that we get an A+ for the scientific response because the decades of investment in basic and clinical biomedical research allowed us to do something that was completely unprecedented: namely, from the time the viral sequence was made available publicly on January 10, 2020, to the time that we had a very well-tested-in-30,000-person clinical trial, a vaccine that went into the arms of persons that was safe and highly effective.

We need to keep the investment in the science to do the same thing with future pandemics, including the possibility of H5N1. The public health response really needs to be improved, particularly. We have, in many cases at the local public health level, some antiquated means of making information available in real time to the people, for example, at the state and CDC level, who are going to be making decisions.

Do you think our disease readiness and our ability to respond effectively are more of a scientific problem or really a human behavior one? And if it’s the latter, how can we address the deep divisions and deep skepticism of science we see in this country?

I think you just hit on the most important aspect of our weakness in response. As I just mentioned, I don’t think it’s scientific. I think we’ve done very well scientifically. I think it is a human element issue. I think the worst possible situation that you can have when you’re in the middle or the beginning of an evolving pandemic is the profound degree of divisiveness that we have had and still have in our country. It’s like being at war. The common enemy is the virus. And we were acting in many situations and in many respects as if the enemy were each other.

Someone, for ideological reasons, not utilizing a lifesaving intervention like a vaccine is tragic for that person and their family. Red states were undervaccinated [against COVID] compared with blue states, which were better vaccinated, and the hospitalization and death rates in red states was higher than in blue states. That is very painful to me as a public health person—that people, good people, got ill and lost their life because, ideologically, they didn’t want to make use of a lifesaving intervention.

The challenge ahead of us now, if we face any other threat such as bird flu, is that people might resist the same public health measures.

I think we have a way to go. We really have very, very much more in common than we have differences. And, you know, ideological differences and differences of opinion are healthy. It makes for a very vibrant society. But when those differences turn into divisiveness, then it gets in the way of what I would consider the most effective response in a public arena for something as devastating as a pandemic.

I did want to talk about some of your early career, especially your work in HIV/AIDS. Like SARS-CoV-2, it was a very new virus, and you received a lot of pushback—in this case from the activist community. How did you gain the trust of people in that community?

I gained their trust because they justifiably were pushing back against the rigidity of the federal government, both in the design and implementation of clinical trials that didn’t take into account the desperate situation that these young, mostly gay men were in in the mid- and late 1980s.

The regulatory approach of the [Food and Drug Administration] was very, very strict and didn’t really take into account the urgent nature of the people needing interventions. So people rebelled. They became confrontative, iconoclastic and disruptive because they wanted a seat at the table.

When the scientific and regulatory community didn’t listen to them, they became very provocative and very disruptive. One of the best things I think I’ve ever done in my life was to see through the confrontation and the theatrics and to listen to what they were saying. And I found very clearly that when I listened to what they were saying, what they were saying made absolutely perfect sense. I came to the conclusion that if I were in their shoes, I would be doing exactly what they were doing. And that’s when I reached out to them, embraced them and brought them into the circle of decision-making about clinical trials. We put them on many of our advisory boards.

It didn’t turn around overnight. It took quite a while, but we went from confrontation to really a productive collaboration that now, 40 years later, some of those people that were so-called rebelling against [us] are some of my closest friends and colleagues. So I think HIV was a very good example of the importance of reaching out to the community that’s involved and listening to what its members are saying.

Finally, what has retirement, or semiretirement, been like? Do you have any hobbies?

No, I’ve never been a hobby person, Tanya. I’m on the full-time faculty at Georgetown University, in the School of Medicine and the McCourt School of Public Policy. When I decided to step down from the NIH, first of all, I wanted to write my memoir. [Since leaving the NIH] I went from dealing predominantly with physicians and scientists who are at the advanced-degree level to working with students at the predegree level, which is really a lot of fun. So that’s what I’m doing with myself, and I’m enjoying it very much.

Listen to an excerpt of this conversation on Scientific American’s podcast, Science Quickly.