A half-century ago humanity sent its first postcard to the stars, carried by a narrow beam of radio waves.

It was November 16, 1974—a turbulent time on planet Earth. The cold war was reaching its crescendo, and the world economy was still sputtering from a Middle East oil embargo that was imposed the previous year. The U.S. had retreated from its crewed forays to the moon but was still fighting in Vietnam, and the resignation of scandal-plagued President Richard Nixon was still reverberating. The Beatles had effectively disbanded earlier yet would officially do so before year’s end. (John Lennon’s solo single—“Whatever Gets You thru the Night”—topped the U.S. charts that very day.)

Against that dark background, this first-ever interstellar transmission was both a literal and figurative ray of light. Astronomers had already started eavesdropping on the heavens, hopefully awaiting murmurs from beyond that would break our seeming cosmic solitude. But this was something different—an intentional summons, perhaps an invitation for communion with hypothetical beings among the stars. Sent using a powerful radio transmitter at the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, it signaled the start of an age that is still unfolding, in which our rapidly changing technological civilization confronts an uncertain fate beneath a silent sky and grapples with how to present itself.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

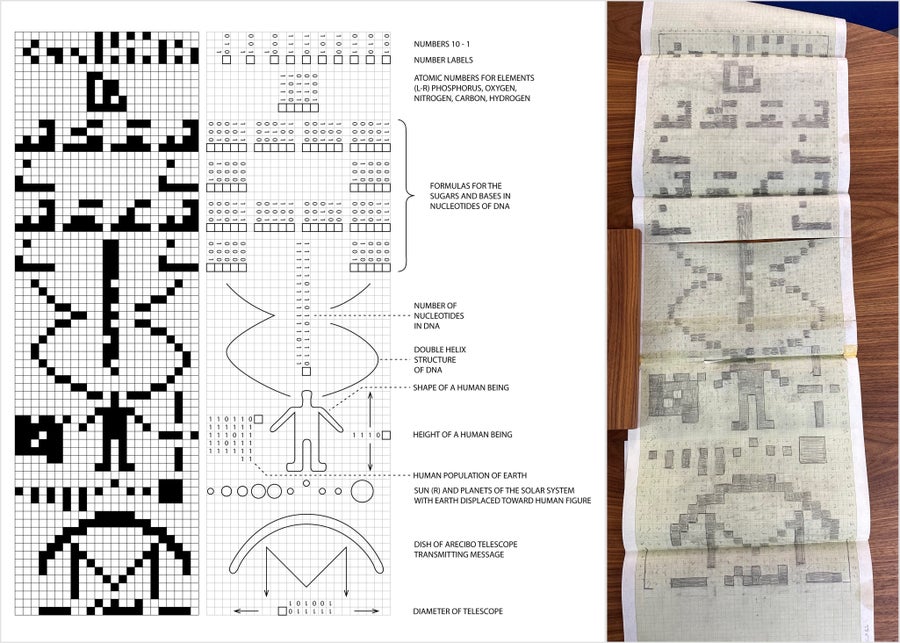

Composed in binary code—a string of 1’s and 0’s—what’s now known as the “Arecibo message” has become an icon of the 20th-century space age in the 50 years since it left Earth. You’ve almost certainly seen it at some point, even if you didn’t recognize it for what it was. Arrange its digits in a grid with the right dimensions, and the transmission yields a two-dimensional image that tells of us humans, our home in the solar system and the instrument that relayed the message skyward.

“I think of the Arecibo message in this grand tradition of attempts at communicating with ET or transmitting things into space that are fundamentally messages, at least in part, to Earth as well,” says Rebecca Charbonneau, a science historian at the American Institute of Physics. But, she says, it’s more than that.

“Human beings are very visual creatures, and we need something visual and beautiful to help channel feelings of spirituality and wonder,” she says. “And I think, in some ways, the Arecibo message is an icon in that old tradition—a visual representation of something that makes us feel small in an expansive and sublime kind of way.”

But just as it symbolizes some sort of transcendence, today the Arecibo message is also a poignant reminder of fragility and loss. Since the message left Earth, the telescope that sent it fell into neglect and eventually collapsed. And the Arecibo message’s designer, my father Frank Drake, died. A few months ago, while rummaging through some of Dad’s old papers, I found an early penciled in draft of the message—along with his musings about the information he wanted to convey and correspondence surrounding its creation. I’d of course known of Dad’s role in sending the message for most of my life, but it was the first time I’d seen any of the work that went into making it. And when I shared an image of the draft on social media, the response was more fervent than I had anticipated, with many folks channeling Indiana Jones: “That belongs in a museum!” (A sentiment with which I agree.)

The Arecibo Message as it appears when its 1,679 bits are properly aligned on a grid (left), an annotated illustration explaining its components (center), and a photograph of the message’s recently discovered hand-drawn first draft (right).

SPL/Science Source (left and middle); Frank Drake (right)

“Those images are seared in the mind of anybody who thinks about this stuff or is aware of the history,” says David Grinspoon, senior scientist for astrobiology strategy at NASA. “It was a very hopeful gesture, and the motivation is transcendent in that it was not for national gain or personal gain. It was like, ‘Hey, humans on Earth, we can do this.’”

With a Little Help from My Friends

Despite its fame, the Arecibo message was not the first deliberate, designed transmission from Earth.

That honor belongs to what is now known as the Morse message, which in 1962 used Morse code to transmit three words in Russian. Designed by three Soviet scientists and sent using a planetary radar complex at Yevpatoria in Crimea, the Morse message was never meant to be received by aliens—unless any of them (improbably) happened to be living on its inhospitable target, the planet Venus. It never even left the solar system. Rather the transmission bounced off Venus and came right back to Earth, where its nationalist sentiments—the words mir (which can mean “peace” or “world”), “Lenin” and “USSR”—were received by its intended audience: us.

“I’ve seen people claim this was the first case of messaging extraterrestrials,” Charbonneau says. “I don’t think you can do that because it’s very clear from the content of the message that it did not have an extraterrestrial audience in mind.”

But, she notes, the Soviet scientists sent the message to commemorate the integration of a new radar array at their facility. “Their gut instinct was to send a message into space,” she says. “And that’s what happened with the Arecibo message as well—to commemorate the Arecibo upgrades.”

Completed in 1974, those upgrades transformed the Arecibo Observatory into a world-class facility for radio astronomy. They included a powerful radio transmitter, as well as a gleaming aluminum surface for the telescope’s 1,000-foot-wide reflector dish. To celebrate those accomplishments, Dad—who was at the time director of the National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center, which ran Arecibo—invited more than 200 people to a ceremony at the observatory, scheduled for November 16 of that year. The transmission would conclude the celebration, demonstrating the nation’s newfound interstellar reach to the gathered VIPs and the world.

A few months before the ceremony, Dad had begun designing the message. It wasn’t his first; years earlier, he’d composed a 551-bit binary message, just for fun, and sent it to the handful of people who’d attended a historic 1961 meeting about the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Properly arranged into a grid, those 0’s and 1’s would form an image that included a human, our solar system, and oxygen and carbon atoms. But only one of the recipients—engineer and technology magnate Bernard Oliver—figured out how to decode it. (Oliver notified Dad with a binary reply of his own: a coded image of a martini glass, complete with an olive.)

For the Arecibo message, Dad constructed his grid as the product of two prime numbers—a rectangle measuring 23 by 73—for a total of 1,679 bits. And then, as he got to thinking about what, exactly, to say, he asked for input from his colleagues—most of whom demurred. Now, somewhat paradoxically, in less than half a century the exact authorship of a message meant to travel for thousands of years—which individuals contributed what—seems to have already been lost to the mists of history. But we know with certainty that Dad was its primary architect and that he worked closely with (among others) Richard Isaacman, then a graduate student at Cornell University. Isaacman offered some suggestions that he recalls Dad adopting, such as making modifications to the binary numbers on the message’s top row and offsetting the planet Earth to indicate that it’s our home.

“I didn’t ascribe a lot of importance to it at the time. I just thought it was really cool,” says Isaacman, who today is retired from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and divides his time between Maryland and Hawaii. “But it was a tech demo that crosses a line into a regime with very profound philosophical implications.”

Here Comes the Sun

Dad targeted a globular cluster of stars called Messier 13 (M13), or the Great Cluster in the constellation of Hercules, because it would conveniently be overhead at the time of the ceremony (nestled in a sinkhole, Arecibo’s giant dish was not fully steerable). In about 25,000 years, Dad’s message will reach M13—or at least part of it, because the majority of the cluster’s thousands of stars will have moved out of the telescope’s beam by then. But anyone who’s around to detect the Arecibo transmission, and who figures out how to decode it, will have a blueprint telling them a lot about us: what we look like, which chemical elements and biomolecules make up our DNA, what our planetary system is and how many of us existed in 1974. Dad’s transmission concluded with a binary encoded representation of the Arecibo dish itself.

“In some ways, it was kind of a love letter to the telescope,” says Kathryn Denning, an anthropologist at York University in Ontario, who studies the scientific search for life beyond Earth. “And that’s beautiful. But this text, this object, this performance has meant so many different things to different people.”

As Dad closed the ceremony on November 16, he told the audience what was about to happen—that they were about to end the proceedings with “a very important beginning.”

“Our Earth, at the present time, on our frequency, is an unbelievable sight. It is presently 10 million times brighter than the sun,” he said. “Anyone who looks in this direction is going to see our star brighter than any other star has ever been, except those others who may have sent intelligent signals.”

And then Representative John Davis of Georgia gave the go-ahead to personnel in the Arecibo control room by paraphrasing a quote from Daniel Webster that hangs in the House of Representatives. “Let us develop the resources of our land and see whether, in our day and time, we might not perform something worthy to be remembered,” he said. “And I think this day we have.”

Bernie Jackson, a heliophysicist now at the University of California, San Diego, had programmed the message into the computer and pushed the button that began the transmission. Outside, speakers blasted audio as the message left Earth—a simple translation of those 0’s and 1’s into two audible tones. The speakers warbled for nearly three minutes, and by the time the transmission stopped, its first bits were nearly at the orbit of Mars.

“What they were hearing was what we might hear from another world,” Dad told me when we discussed the message on its 40th anniversary. “It had the aura of human beings doing something marvelous that involved the whole cosmos.”

Across the Universe

Dad’s transmission was, in some ways, from a more innocent time that was less plagued by cosmic paranoia. Few people opposed it for the seemingly remote possibility of summoning malevolent alien invaders to Earth. But even so, not everyone was particularly pleased with the experiment, and over the past 50 years, a lively debate has sprung up regarding the ethics of interstellar messaging. Some opponents consider it a dangerous practice that might attract the attention of civilizations bent on destruction; others are more concerned with who gets to decide what we send, in addition to what we actually say.

“Now that we know about exoplanets and potentially habitable planets within several light-years, it’s not as outlandish to think that there could be a consequence of sending something and that we could, in our lifetimes—or in the lifetimes of our close descendants—receive something back,” Grinspoon says. “But I’m still of this optimistic mindset that if we did get the response to something, it would be the most wonderful thing ever—not just cool but potentially transformative in a really needed, exciting and hopeful way.”

Frank Drake, the visionary astronomer who designed the Arecibo message and helped begin the scientific search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

Ramin Rahimian for The Washington Post via Getty Images

But such worries haven’t kept Earth quiet. Every day we release into the cosmos our own “technosignatures” of all sorts, any number of which could conceivably be discerned with the appropriate toolkit across interstellar distances. And since the Arecibo transmission, at least two dozen additional intentional messages have been loosed upon the sky. These include additional transmissions sent from Yevpatoria, a Beatles song, a Doritos advertisement and a series of signals to the TRAPPIST-1 system of seven tantalizingly Earth-size planets. Today, Denning notes, the ability to send interstellar transmissions is no longer limited to government-operated facilities—and it’s likely that we don’t even know of all the messages that have been beamed from Earth. And maybe, despite the narrative in Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem, that’s not a bad thing?

“If everybody in the galaxy keeps quiet, we never figure out if we are alone,” says Jonathan Jiang of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who, along with his colleagues, has designed an upgraded version of Dad’s interstellar memo. “Communication is the key to figuring out whether there’s anybody out there.”

Hello, Goodbye

In the end, if we receive an answer to the Arecibo message telling us that we are not alone, it won’t happen in our lifetime—or even in the next millennium. Traveling at the speed of light, it will take that message some 25,000 years to reach the outskirts of M13 and at least another 25,000 years for any potential reply to reach Earth. “Will there really be anybody here to reply to?” Denning asks. “I don’t know if that’s a question they would have asked, apart from the nuclear war aspect.”

That Dad and others were even considering a project that might unfold on such an extended timescale reflects a maturity in thinking that was perhaps a bit unusual for the 1970s, Grinspoon says.

“That forces you to imagine our own longevity in a way that almost nothing else makes us think of,” he says. “What else do we do that we have to think of the consequences 50,000 years in the future?”

Searching for life beyond Earth is, in some sense, an exercise in optimism. It requires that you imagine there is something, or someone, to be found—and that we humans are capable of making that discovery and reacting accordingly. As some have said, as long as we are listening for whispered signals from distant civilizations, announcing our own presence is a moral obligation. (And Jiang also told me that making cosmic messages can be an exercise in helping humankind’s moral advancement, pushing us to grow out of the conflicts that now so consume and threaten our world.)

But the messages we send to the cosmos, even the Arecibo message, are fleeting. From afar, they are Earth revealing itself for mere instants, as some beaming declaration that briefly outshines the sun and most everything else on some snippet of the electromagnetic spectrum. And then the planet goes back to black, just another silent world among billions in the Milky Way.

With my father having fallen silent, too, I sometimes find solace knowing there’s some small part of him still out there, forever traveling. Frank Drake never left Earth, yet his message—our message—is now 50 light-years away. More than 1,000 star systems reside in that volume of space, a vastness so easily lost in our galaxy’s billions-strong stellar swirl. In that murk, we know of only a few that are in the transmitter’s beam, although so far no one has echoed in reply. Chances are, none ever will. But that didn’t stop Dad from searching, or from seeking some cosmic connection. Too many secrets remain hidden among the stars. And we still have so much to say.