LIVERPOOL, U.K. — On most days of the year, the streets of this historic English port city are bustling with tourists from all over the world, attracted to its illustrious music heritage. Mainly, they come to see key locations in The Beatles’ story, spots like The Cavern Quarter — home to a faithful reconstruction of the Cavern Club, where the Fab Four famously cut their teeth — and the childhood homes of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, both carefully restored to their 1950s and early 1960s period finery.

But for the past few weeks, John, Paul, George and Ringo have been overtaken as Liverpool’s number one music tourist draw by another also hugely popular — and to many onlookers, baffling — cultural behemoth: The Eurovision Song Contest, which took place earlier this month in the city’s 11,000-capacity M&S Bank Arena, located on the city’s waterfront, next to the River Mersey.

Sweden’s Loreen won the annual competition with her song “Tattoo,” becoming the first woman and only the second person to collect the prize twice.

In all, 37 countries took part in Eurovision, including hosts the U.K., as well as France, Germany, Italy, Belgium and Australia, watched on by an estimated global television audience of more than 160 million people. (Official viewing figures are yet to be released although they are expected to be higher than last year when 161 million people tuned in across 34 countries, according to organizers the European Broadcasting Union).

For Eurovision fans, who enthusiastically flocked to Liverpool in the tens of thousands, the consensus was that this year’s contest was one of the best in the event’s recent history with many attendees praising the calibre of artists participating, slick live show production and the warm welcome from Liverpool.

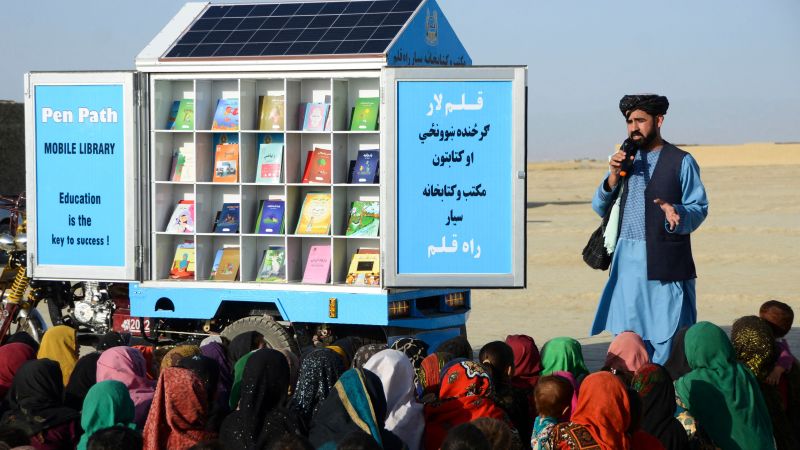

Remembering Ukraine

The United Kingdom, last year’s second-place finisher, hosted 2023’s Eurovision Song Contest on behalf of war-torn Ukraine, which won last year’s competition with “Stefania” by rap-folk band Kalush Orchestra. It was the first time the country has held the event in 25 years; organizers pulled out all the stops to ensure the 67th edition struck a balance between camp fun-time party and honoring Ukraine’s culture and people.

This year’s theme was “United by Music” and throughout Liverpool a colorful array of Eurovision banners and Ukraine flags were on proud display. The city’s bars and restaurants updated their menus to sell dishes and drinks named after famous past Eurovision songs (a cocktail named Puppet On A String, named after the U.K.’s 1967 winning entry, sung by Sandie Shaw, and costing £10.00 [$12.50] quickly sold out at one venue). The windows of shops were filled with blue-and-yellow scarfs, hats, fridge magnets and flags, alongside the usual Beatles and football souvenirs. Even HMS Mersey, a Royal Navy ship temporarily docked in the city, was lit up in the Ukrainian colors of blue and yellow for the weekend.

People queued to snap up everything from sequin covered pom poms to pink tinsel wigs at official Eurovision merchandize stalls. Local clubs, pubs and bars advertised their own Eurovision parties, authorized and unauthorized, as music — mostly Euro chart pop — played everywhere you went. (For the second year running, TikTok was an official partner of Eurovision, sponsoring TikTok-branded performance spaces around the city, as well as hosting in-app livestreams and exclusive performances).

Loreen wins The Eurovision Song Contest 2023 on stage at the Grand Final at the M&S Bank Arena on May 13, 2023 in Liverpool, England.

Dominic Lipinski/Getty Images

Early figures from local authorities indicate the contest brought an additional 500,000 visitors to Liverpool over a two-week period, compared to the expected 100,000. Prior to the start of Eurovision, Natwest Bank estimated tourists would generate around £40 million ($50 million) in spending with demand for hotel rooms and visitor accommodation exceeding supply.

Aside from main song contest, host cities run a busy calendar of sister events. In Liverpool, those included The Eurovision Village, a dedicated 25,000-capacity fan zone in the city center, located around 15 minutes’ walk from the M&S Bank Arena, which ran a program of mostly free-to-attend DJ sets and live performances.

On the night of the Grand Final, entry to the Eurovision Village to watch a live screening of the competition’s climax cost £15.00 ($18.00) with all tickets selling out well in advance. By comparison, tickets to watch the Grand Final at the M&S Bank Arena ranged from £80.00 ($100.00) to £380.00 ($475.00) with VIP suites holding up to 12 people costing £45,000 ($56,000).

Despite the high prices, tickets for all nine live shows — comprising six public dress rehearsals, two televised semi-finals and Saturday’s Grand Final — sold out in 90 minutes, according to host broadcaster the BBC (the show’s vast staging and production requirements cut the arena’s 11,000-capacity almost in half with 6,000 tickets available for each show). The British government made an additional 3,000 tickets available to displaced Ukrainians living in the U.K. at a cost of £20.00 ($25.00) per ticket.

Driving fan engagement

The list of what separates Eurovision from other music entertainment shows is long and packed with unique curiosities, including over-the-top songs (Croatia’s Let 3 took this year’s novelty crown) and an abundance of eye-catching costumes that veer from fetish latex wear (as worn by Germany’s glam metal band Lord of the Lost) to ’70s-style sequin-covered jump suits (Ireland’s Wild Youth). Eurovision fans delight in replicating their favorite performer’s look. Finnish runner-up Käärijä’s distinctive costume of spikey black trousers paired with green bolero sleeves was an especially popular choice in Liverpool.

Eurovision fandom among the LGBTQI+ community is at the heart of its huge popularity. In 1998, Israel’s Dana International made history as the contest’s first trans winner. Although politics is largely banned at Eurovision (The EBU stopped Ukrainian president Zelensky from addressing the event this year), it has long championed LGBTQI+ performers and representation – often in defiance of conservative Eastern European countries where homosexuality is discriminated against such as Russia and Hungary, both of which no longer participate in the contest. (Russia was banned following its invasion of Ukraine. Hungary withdrew from the competition in 2019 amid an increase in homophobic rhetoric from the Hungarian government).

Eurovision’s organizers are keenly aware of how integral LGBTQI+ fans are to the event’s success and work hard to ensure it is a safe and welcoming place for everyone. That was evident in Liverpool, where queer culture featured prominently, both in the contest itself and in official fringe events like EuroCamp Presents, a free three-day LGBTQI+ focused festival featuring drag, dance, vogue and music. Liverpool drag performer Danny Beard stepped onstage at the Euro Village on Friday, looked out at the audience and described Eurovision as being “like Gay Pride on crack.”

Eurovision also stands out for how closely it involves super fans. Organizers accredited over 1,100 journalists from over 50 countries to cover this year’s event. Of those, around 180 were from what organizers term ‘Fan Community Media’ — representing the biggest international fan sites, social media pages, magazines, bloggers, vloggers and outlets dedicated solely to the Eurovision Song Contest. Another 550 journalists, half of which were from fan media outlets, were accredited to cover the event online.

Eurovision fans around Liverpool City Centre ahead of the semi-final of Eurovision Song Contest at the M&S Bank Arena in Liverpool.

Peter Byrne/PA Images via Getty Images

In the media zone, located inside a huge conference hall next to the M&S Bank Arena, fan community journalists were grouped together near the entrance, bringing a buzz and energy (and loud singing) to the press room that’s often missing from large-scale entertainment events.

Artists feel the Eurovision love

While many viewers in the United States and United Kingdom have long regarded Eurovision as little more than cheesy entertainment — a reputation organizers acknowledge and play up — the song contest’s enormous audience gives it an unrivaled reach as a marketing platform. Thanks to streaming, artists like Warner Music-signed Käärijä, one of the biggest breakout stars of this year’s Eurovision, can go from virtual unknowns to overnight sensation.

At the start of the year, Käärijä, who finished second behind Loreen in Liverpool, had around 1,500 followers on TikTok. After the competition, he had over 440,000. His runner-up song “Cha Cha Cha” has been streamed over 39 million times on Spotify and the video for his Grand Final performance has drawn 9.9 million views on YouTube.

Universal Music-signed Loreen was already a star in Sweden going into this year’s contest, having first won it in 2012, but she received a massive spike in streams following her final performance. Her winning song “Tattoo” has generated more than 76 million streams on Spotify, cracking Spotify’s Global Top 50. On May 14, the day after Eurovision wrapped, Loreen broke the global Spotify record for the most-streamed track in a day by a female Swedish artist.

“Nothing can get you in front of a bigger audience,” Netta, a 2018 Eurovision winner for Israel, told Billboard backstage, prior to performing in Saturday’s Grand Final, where she sung a cover of Dead or Alive’s “You Spin Me Round (Like a Record).”

“There is something inspirational about this event,” she says. “It shows how magical humanity can be… It’s the kitschiest, most dramatic, funny circus, but it’s also genuine.”