Womb City, the debut novel from acclaimed short fiction writer Tlotlo Tsamaase, is described as “The Handmaid’s Tale meets Get Out” and a “cyberpunk body-hopping Africanfuturist ghost story.” In other words, this is not your typical dystopian mystery, and io9 is thrilled to share a first look.

Here’s a description of the story:

Nelah seems to have it all: fame, wealth, and a long-awaited daughter growing in a government lab. But, trapped in a loveless marriage to a policeman who uses a microchip to monitor her every move, Nelah’s perfect life is precarious. After a drug-fueled evening culminates in an eerie car accident, Nelah commits a desperate crime and buries the body, daring to hope that she can keep one last secret.

The truth claws its way into Nelah’s life from the grave.

As the ghost of her victim viciously hunts down the people Nelah holds dear, she is thrust into a race against the clock: in order to save any of her remaining loved ones, Nelah must unravel the political conspiracy her victim was on the verge of exposing—or risk losing everyone.

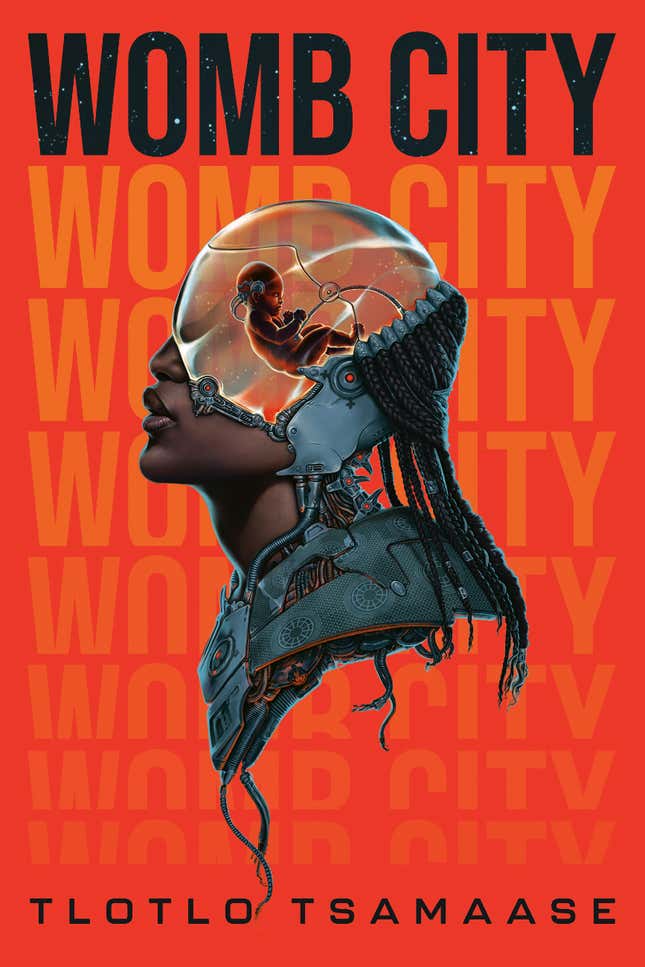

Here’s the full cover; the artist is Colin Verdi, and the designer is Samira Iravani.

“My jaw dropped when I saw how Colin Verdi drew from the details in Womb City by blending its science fiction features into this surreal mind-womb: a disembodied, floating cyborg’s head that encloses not a brain but a womb-pod with a baby trapped inside,” Tsamaase said in a statement provided to io9. “This image is truly symbolic of the objectification and pervading threat that Nelah, the protagonist, faces. I love the striking aesthetics of the mind-womb—particularly how it touches on the book’s themes of restricted autonomy and the technology that plagues the characters’ bodies—against this red backdrop; this color transforms Womb City’s cover into a horror-hued poem.”

Verdi gave us a bit of background on how the cover came together. “When I started working on Womb City, I was lucky to receive a gorgeous moodboard from the author that painted a clear picture of the visuals Tlotlo Tsamaase had had in mind while writing this story,” the artist said. “It included the phrase ‘Womb of Sins’ tucked under a series of reference images of people growing in pods. The imagery that would end up on the final cover immediately sprang to my mind. The titular womb is directly where the central figure’s brain should be, telling readers that this is a story about a mother with a child always on her mind, yes, but also conveying that this book is about how a secret or a sin can grow and take on a new shape the more time it spends rattling around in our heads. The mother’s body is incomplete, with the creeping tendrils of wires and futuristic technology dangling from her ‘shoulders’ into space, to show how much this thing growing in her mind will consume her.”

And here’s an excerpt from Womb City!

SUNDAY, AUGUST 2

05:00

PURE

In our city, everyone lives forever. But murder hangs in the air like mist.

The morning sun is a still-sparkling eye, blinking through our bedroom shutters when my husband shrugs me awake. “It’s time,” he whispers.

I toss and turn. Sleep slips, evades me. Eyes closed, the skin of my eyelids is tinged pink as the probing, UV-forensic sunrays seep into the darkest part of my mind, the part that wakes up with me every morning. Barren. Lonely. Desperate. I rub the heels of my palm into my eyes.

“Babe.” Elifasi’s lips nibble my earlobe.

I sit up as my microchip vibrates, sending quivers down my spine. It’s my daily reminder for my morning assessment. I already feel so incarcerated in my own bed that the government-imposed reminder makes me grit my teeth.

“I don’t understand why you always feel nervous about this daily routine,” he says, fluffing the pillow. “You always pass.”

“You don’t understand what it feels like to lose a body,” I bite back. “What if I had a child?”

Child. That grenade of a word in our marriage lands in his heart, blasting out pieces of sadness like shrapnel. The hurt in his eyes is too heavy to hold. But what if I bump into them at the market, and I can’t tell that I gave birth to them in my previous life? I do not say these things aloud.

His hand detaches from my face. The cold air fills his place, gripping me. The vast amount of space between us keeps us emotionally light-years apart. My fingers clasp his cotton shirt at the small of his back, where I often draw circles to comfort him, but he shrugs me off. “I’m sorry.” The wet whisper clings to my lips. “It’s just … I wish the Body Hope Facility had given me a body that was at least fertile, given the high premiums I pay.”

“We,” he says.

“What?”

“We pay, not I pay.”

I make more money than him, and he says I keep rubbing it in his face, wrongfully accusing me of doing so. I wish he would see past that because it makes it difficult to speak to him.

“I’m sorry,” I whisper.

“It’s a waste of time to focus on the past,” he says. “The only thing we can change is our future.”

Sirens pierce through the silence in our bedroom. He stands, the bedcovers crinkling. His fingers tease open the shutters as he peers at our garden down below. “Looks like it’s about to rain.” The city sirens are hollow ghosts, fingering the city along the A1 highway, pulsing through our suburb, Tsholofelo East, toward a culprit.

Murder hangs in the air. The cold clings to my skin. Every Sunday at the cusp of dusk, each police tower in every district coughs up into the skies a puff of human corpse-detecting chemicals. The rains will come, and the chemicals will detect homicide in our urban landscape. Through the sliver of window to the horizon, far out, is a scenic view of soft hills and sky, a mass of forested land, outstretched.

“It must be the perpetrator they brought in last night,” Elifasi says. “He wouldn’t talk. Previous forensic assessments failed to predict his criminal intent. But the sun never fails us.” Its rays catalyze the chemicals into truth-seeking action. He directs this statement at me. The guilt, the anger bridling beneath all that muscle, those still-murky deep-set dark eyes. A ray of light knives its way across his light-brown skin, climbing up his sharp nose. His hand jerks; the wooden shutters jolt and flick open. The sun glares into my face. Guilty, it seems to say.

“Even if the sun fails us,” he says, “we can always rely on the Murder Trials to protect us.”

I tremble. The Murder Trials, heavily shrouded in secrecy. It’s a back-up plan for our forensic evaluations and allegedly uses horrid practices to catch criminals who go undetected by technology—practices I pray I never discover. They especially scrutinize microchipped people, which means a high majority of women, since female bodies are microchipped more often than men’s. But I’ve no idea what they do to people like us or why they target us. How can I avoid what I don’t understand?

The Murder Trials are based near Matsieng, a ritualistic site made holy by the surrounding folklore-riddled waterholes, where some crazy people drink its miracle water to solve financial problems, infertility, erectile dysfunction . . . I’m no atheist, but I can’t believe a whole-ass government would entrust our safety on supernatural gimmicks. How could crevices in the ground aid them in unearthing criminals? Yet even I can’t deny it’s worked so far, reducing crime over the centuries.

Elifasi pulls me to my feet. “Let’s get this over with,” he says. I lean in to give him a morning kiss, but he evades me.

“Sit.” He presses me primly against the armless cushioned chair. He walks behind me, footfalls softened by our lush bedroom carpet. Crouches by the bed.

“It’s chilly in here,” I say, bare-armed, bare-legged, in a light velvet camisole and pajama shorts, trimmed with satin.

His hands brush my shoulders, my neck, holding me stiffly. “Shit.”

“What?” I ask.

He fingers the Plasma hanging above our dresser. “Ran out of memory. It’s not automatically connecting to your microchip. Why can’t it find you? Told you we should’ve gone with a different brand.”

“Just plug the cable in,” I say.

He yanks an audio-video interface cable from the dresser, wraps it around my neck. “Been naughty or nice?” He chuckles, and lets it fall loosely around my shoulders.

“Both,” I add for the fun of it.

Reality strikes me. I freeze, unable to move, as a cold draft of fear settles in my lungs, and I realize with rising panic that I will never escape this invasive ritual.

His thumb presses against my lip. “You taste like gunpowder,” I whisper.

He smiles, inserts the stiff, cold, serpentine cable into a slim port sitting below the AI microchip that’s fitted in the back of my neck. He inserts it the same way he uses his penis: mechanically, thoughtlessly. I jerk from the shock of the cable’s cold, abrupt slurping of my memories straight into our Plasma’s storage facility. Every morning, I have an AI assessment where my husband peruses my memory files. “That’s why I married you—to keep you in line,” he’d shoot off, laughing at his own joke.

The cable connects to the Plasma and transmits data recorded by my eyes from the past 24 hours, like Sunday movie night. He sits on the edge of the bed, gulps a cold beer, by the glow from the Plasma’s screen. He rotates his finger. A silver remote clipped to his index finger fast-forwards through the scenes, rewinds, freezes the frame of a man at a conference, sitting next to me: honey-gold eyes, bronze skin, crew-cut crow-black hair, a tickle of flirtation in his smile. Janith Koshal. A smoking hot motherfucker. I remember his tongue decanting orgasms from my body.

Fuck. I must not think of him else a detection alert will prompt Elifasi of the memory triggered by a rising heart rate, dilated eyes and whatever the fuck bio signals are currently being transmitted. I slow my breathing, quickly recall the most mundane episode of taking the trash out from the kitchen, focusing my minds’ eye on the garbage bag swelling with heaps of disposed food, the smudge of avocado on the sharp edge of canned beans, the stink of rotting meat—

“Nelah, who’s that?” Elifasi asks, heating the air between us with a smog of jealousy.

“Mm, don’t remember.” I curl and uncurl my toes against the woolly carpet. “Jan-something. VC investor in construction tech. Our firm’s using one of his entrepreneurs’ products.” Our usual chitter-chatter dinner of interrogation.

He follows my conversation with Jan, which echoes throughout our room like the pilot of a drama, cinematography crisp. Jan leans forward, caught in the golden dusk, taps his finger on my wrist, imparting a meeting into my calendar like nanobots into his bloodstream—it appears on the tiny screen on his wrist, and he smiles. “Then why does he want to meet you late at night?” my husband asks.

“Because I run an architectural firm,” I say, masking the memory of our rendezvous with the mental image of the garbage bag in our kitchen. Eli stares at me, waiting for more. “It was a meeting for a project, and it wasn’t late, it was at 5 p.m. He and his wife bought a stand in Mokolodi. They’re looking for an architect to design an eco-conscious home for their ever-expanding family. And since I won Architect of the Year Award for world-class sustainable designs, I’m the best architect for the job. Hence …” I point to the screen, exhausted from the amount of labor it takes to hide a secret, and sighing at the effort of having to always ad-lib lies.

“Oh …” Thumb against the remote, he presses play.

“You’re supposed to scan my memory files for undetected infractions.”

Elifasi shakes his head. It takes two hours of him scrolling through my memory files as I pass time by fiddling with the hologram 3D design for a museum that my firm will be presenting to a client this week. But I can’t concentrate. I stare at him and wonder if every marriage is like ours: microchipped wives watching our husbands disembowel our thoughts and memories, dissecting our every infraction, interrogating us about our glances, our clothes, our conversations. Monitoring us for undetected crimes. Invading our privacy for the sake of public safety. My nails dig deep into my skin as a scream roils inside my throat—the scream, afraid to get out. We’re not only losing the power of our bodies, we’re losing the privacy our minds. What will be taken next for the sake of safety? This microchip protects our city, but it’s the husbands, the city, the government’s tool to get inside us. My husband has the upper hand in our marriage, because I’m the one with a criminal body.

He stares at me, smiling, unaware of the volcano erupting within me. These intimate sessions mutilate my sense of independence; in this murdered church of my body, every molecule is a screaming prisoner.

I face our slim window. The horizon between the hills and sky is hazy as the sun continues burning like luminol through the city’s air, activating chemicals leading to an untold crime. Which murderers or buried bodies still hiding in the nooks and crannies of the city will be found today?

It doesn’t matter, as long as it’s not me.

Sometimes it turns me on, the gluey mixture of fear and pleasure in the minimal tactility Elifasi gives me when he connects me to our home system. It’s our foreplay. After this, like always, we have sex. Pump, pump. Tap out in four strokes. Cum. Done. Unsatisfactory. My body’s sexually frustrated. Elifasi stands, shakes himself out. “Finished. So far, you’re pure.”

Mxm, bastard. As if it’s his dick that purifies me. No, I don’t hate my husband—I just casually and occasionally call him a bastard, with … love. My thoughts might leak into our home cinema, leading to a long interrogation by my husband, the formidable Elifasi Bogosi-Ntsu, well known at the force for his scathing ability to gouge out the truth from the mouths of perpetrators, and even his wife.

He pulls on a dressing gown. “Next task.”

We walk into our spacious closet, fitted with mirrored closet doors. A slim biometric scanner is embedded in one of them. I push aside my curtain of Senegalese braids, exposing the back of my neck and the microchip. He slides his hands down my bare arms, giving me chills, and presses my palm against the mirror. Its surface ripples, fibrillating into horizontal lines that break into patterns of sound waves as the AI microchip assessor’s disembodied voice echoes through the closet in a monotone: “Dumêla, Nelah,” she greets. “How are we feeling this morning?”

Her voice echoes through the room, but I stare steadfastly into the mirror. “Tired. Please scan my microchip.”

The mirror launches into a series of questions that are meant to assess my responses. “Have you been feeling unlike yourself lately? Are you experiencing any sociopathic tendencies?” The vibrant blue sound wave patterns recede into the mirror.

“No,” I say. The lines are steady. “No.”

“Have you committed a crime that the microchip failed to detect?”

“No.”

“Have you recently experienced unexplainable bursts of anger or other emotions?”

“No.”

“Have you experienced any problems or malfunctions?”

“No.”

“Good. You are required to obtain your next dose of medication from the Body Hope Facility within seventy-two hours.”

“Thank you. I will do so.”

“This is also a kind reminder that you have your forensic evaluation this Wednesday at 16:45 p.m.”

How could I ever forget? It’s my nightmare. “Thank you.”

She’s interrogated me before, in the days after I came home from the hospital after my consciousness was transplanted into this body. It felt just like the day after I gave birth to a still-born child. Everything was sore and raw, my body thin and famished. She has a database of my physiological responses as benchmarks, and my current responses are charted on the mirror by an invisible needle. The needle moves erratically if I lie.

She reports my results: “Your physiological responses are steady and indicate no signs of deception.”

I am perfect. I am innocent. I am pure.

MONDAY, AUGUST 10

08:00

THE BLACK WOMB

This is my third lifespan.

Since there’s no record of an eviction for criminal reasons, the original owner of this body must have willingly evacuated these skin and bones at the age of eighteen for reasons I’m not privy to, but her parents continue to love me as if I’m their original daughter. The second host was evicted for a heinous crime. As per my country’s criminal legal regulations, my body is fitted with a microchip that observes my behavioral patterns to deter criminal recidivism. It is an operating system, implanted in my brain stem to remotely control my body during criminal activities.

Privacy violations are rife on such bodies until the assessment of these bodies confirms their purity, which can take anywhere from a couple of years to decades. My purity test is close, but we’re neither given an exact date nor told what to expect, much like the forensic evaluation. Passing the purity test means I could ultimately be free of the microchip. I’m terrified that one tiny wrong move could destroy my chances. I need to be perfect. I need to be perfect. I must be perfect.

One day, I’ll be free.

But how can I be free when my womb is a grave, killing any new life that tries to form, any seeds that my husband plants in it?

A black cloud hangs over me. We lost the fetus during our first round of IVF, and now we trundle about the house, broken and forlorn, having thrown all our savings at it. I didn’t pay the alarming cost for mind transfer reincarnation to receive an infertile body with an amputated arm, even if it is a surgically-attached, fully-functional bionic prosthetic. I couldn’t tell it apart from the rest of my body until my doctor peeled back the synthetic skin to show me, the first day I was revived. But I don’t know why this arm was amputated; my parents won’t tell me what happened to their first daughter in this body, so I don’t know if it’s the first or second daughter who lost this arm, and how. I feel robbed. I filed a report against the Body Hope Facility (“The Body Hope Facility. Body hop, body hope; we give every soul hope.”) But it’s in their indemnity clause, which allows them to supply bodies they deem in perfect condition, not what the host considers perfect; there’s nothing I can do.

It’s back to the old routine now, the ovulation alert waking us to morning darkness. Elifasi thought it’d be exciting to do it in the shower, the one thing we can vary, the only thing we can control in our lives. Suddenly he wasn’t in the mood, so I said, “Just stick it in and cum. It’s not like you ever last anyway.” His mouth puckered. He hammered me. I leaned against the cold tiles, zoning out into an out-of-body experience. I was a robot; the sex was mechanical.

I’ll need to work something out so he forgives me for my quippy remark.

I was pregnant before, for five months. Second trimester. We were glowing, more in love than ever. As a parent, all you think about is how you’ll protect this newborn once it’s outside the safety of your body. That’s all we fussed about, purchasing nanny cams, baby monitors, an AI tool that would monitor his little breaths. A surgically installed GPS app tagged into his nervous system, just in case we lost him. I’d read terrifying stories of newly-minted parents losing a baby, forgetting them at the mall. Such a horrid thing for a parent to do. That would never happen to us.

But we lost our little boy. Within the boundaries of my body. Inside me, not away from me, not forgotten in some random place, but right beneath my skin, below my heart.

You just never, ever think that your baby could die inside you and you wouldn’t be able to tell. To be pregnant for five months—then to come home three nights after an emergency induced labor with an empty, scraped-out womb, holding that blanketed, precious stillborn—is devastating.

01:34 a.m., when the dead fetus was removed. Intra-uterine fetal death, they called it. I gave birth to a dead child.

I have given birth to three dead children.

What was worse was that fed-up, “I don’t know what’s going on but something smells funny” look of betrayal my husband shot at me. “Really? You couldn’t tell you were carrying a dead baby? Our baby. That you’ve been throwing money at the fertility center to have. Didn’t you find it strange he wasn’t kicking? For three fucking days. Jesus Christ, you killed my son.”

The memory of it sends panic blazing through my body. I didn’t drink, I didn’t smoke, I didn’t overwork. I ate healthy, I exercised mildly, I came home early. I did everything right. I paid my taxes, as if that should have a bearing on my fertility. My husband later apologized, but you can’t erase what’s said, what’s done. Words leave a certain damage, just as much as a bullet in the flesh.

I’d stared at the fresh white lilies drone-delivered to our home, tagged with a note: From the Koshal family. We’re terribly sorry for your loss. Our family’s hearts are with you. Anything you need, please don’t hesitate to call. Only, I know he sent it, not his wife, like she’d give a damn about my pregnancy loss. He must have done it behind her back, she’d never allow him to send another woman flowers. I know he meant it, too. I glare at my husband, and sometimes I wish he was another man named Janith Koshal.

I shuffle into work, sleepwalking out of the elevator. Jan’s message is the first to come through. Morning, had a dream about you last night. Link up? I ignore it. I need to stay away from him. But we run in the same business circles, so we’re bound to bump into each other. I married someone I need to stay loyal to. Jan’s married, too, with twins, and that’s what I envy, what he has, which makes me appreciate the natural way he flirts with me… it turns me on, turns me—the robot who’s been malfunctioning for years—on. I hate to think this but

what if,

what if,

what if

Jan can impregnate me?

I know the doctors at the fertility center said I’m infertile, but that “what if” is making me think terrible things. Maybe, just maybe… it’s not me who is malfunctioning, but Elifasi.

I lazily press my finger against the biometrics scanner. I yawn as the door buzzes me into the open-office plan of the glitzy Gaborone School of Architecture (GSA). I gulp down coffee that’s not pumping any effective caffeine in my system. Most of my colleagues are hyped, but some are agitated about the board meeting regarding student marks, absences, failures …

My back stiffens when an early-bird student trudges in, one hand pressed against her arched, aching back. I’m teaching several courses as an architectural design lecturer. On the days I’m on campus, I see pregnant freshmen traipsing through hallways, courtyards, into our offices begging for marks and submitting late coursework. I want to scrape out the fire of pure anger that devours me with my nails and teeth. Because I hate it. I hate how easy it is for a child to have a child. They’re too young to take care of themselves, let alone a baby. It’s amazing how it happens: you just fuck and you’re pregnant. The ease and simplicity is so foreign to me. As if my body is made to just have sex without leading to procreation, like I’m being punished for being successful in other areas of my life. On gossip rags that often demonize me for owning a criminal body, they started calling me the “Black Womb.”

I came home one day to find my husband yelling at someone, who works at the latest culprit newspaper, over the phone. “… So heartless,” he screamed. “So despicable and insensitive of you, publishing clickbait articles on our pain, my wife’s unimaginable pain, after all the humanitarian work she does.”

Mxm, what a hypocrite. Everyone thinks he’s the perfect husband, protecting me. It’s not me he’s protecting, it’s his reputation. In the privacy of our home, no one sees him yell at me out of frustration over how embarrassing it is for him to have his wife’s image shamefully spread across these news sites.

He doesn’t care about my fucking tears. I’m just cheap, dirty laundry tarnishing his image.

#

At the table in my parents’ backyard during our lunch is my parents, Limbani and his wife. For the third time in a row my husband’s absence is devastating, much to the pleasure of my brother. Jan’s text buzzes in. My wrist itches with the neon-blue words: 1 UNREAD MESSAGE.

What are you afraid would happen if you responded? I am worried about you. Concerned. Forget my feelings for you. I just want to make sure you’re okay.

Our relationship has been solely a two-year emotional affair that was only consummated once. After I crossed that boundary, I resisted ending up in bed with him again, and I thought he’d grow impatient, consider that fuck a conquest, and leave. Instead, we simmered in our reciprocal adorations, making me a sun of his world, his heart. I drew back, afraid of what we were becoming. I used to wonder, “Why’s he still here? Men don’t do that unless they think I’m an exciting challenge: the married woman who keeps saying ‘no’.” Even though I know that’s never been true of Jan, to push him away, I childishly respond in a fit of frustration:

Find a fuck-buddy elsewhere.

Just as I’m about to switch my phone off, his message comes through: My wife started off as my fuck-buddy, I learned my lesson there. I’m not just attracted to how beautiful you are, I’m attracted to your intelligence, the work you’ve done in this industry.

My heart stops in my throat when his last message comes through: I’m getting a divorce. Not for you or anyone. For me.

So the rumors are true. How brave he is, I think—which is strange. Why do I think that? Do I want to leave my husband? Am I a coward then, for staying in this marriage?

Pouring himself wine, my brother, Limbani, continues his incessant verbal attacks on me whilst the rest of my family tiptoes around any mention of babies. Limbani was furious when he overheard me call his sister’s body infertile. I was broken, confiding in Mama. He called me ungrateful, a stupid, spoiled brat for disrespecting his sister. He will never ever accept me.

Limbani slices into a piece of his medium-rare steak, and I stare squeamishly as blood oozes onto the white porcelain plate. He scrubs the blood clean with a cushion of meat, chucks it into his mouth, and says, “With the astounding advancement of science—we can even upload our consciousnesses into other bodies!—there’s just no scientific reason for a woman to be unable to have kids. It just doesn’t make sense. My wife’s been brilliant so far. Given me three healthy kids. Isn’t that right, babe?” He glances at her with a smirk. She looks terribly uncomfortable, busying herself with getting salad.

“Nana,” Mama says as she places her hand over mine, the other cradling a cup of roobois tea. “Isn’t there a way for the doctors to perhaps transplant the consciousness of the stillborn child into another body?”

Limbani laughs, and he’s got the yak incessantly flowing in his wine glass, tipsy as fuck. “God, Mama, no one’s donating newborns as body supplies! They’re too young and not eligible for the process.”

“Well, couldn’t they transplant your baby’s consciousness into an older body? Maybe a teenager’s body.” She stares around the large table, but everyone avoids eye contact with her. “Aren’t they supplying them nowadays, huh mogatsaka?” She turns to Papa, who looks just as uncomfortable as the rest of us, unable to offer her a lifeline.

“Ja nè. Maybe she can’t fool her body like she fools us,” my brother’s voice booms, and I close my eyes waiting for the blitzkrieg. “Maybe, like I’ve been saying, they pumped a man into my sister’s body.” His sister’s body is my body. My body. “I’m right, ain’t I? You’re a man under that skin. It’s all unnatural.” He points his fork at me. “And because of that, you angered the ancestors. They must be punishing you by not allowing you to have kids. A life for a life.”

He hates me more than the devil, but that’s low, celebrating the fact that innocent babies have lost their lives. My babies.

“I mean, look around the table,” he continues. “Where’s your husband? Always busy. Always absent. Only a real woman can keep a man around.”

I leap forward, fueled by loss and anger, my knee crushing the center of the chocolate cake. “You misogynistic bastard!” There’s a knife in my hand, raised to stab him. My other hand wraps around his throat, which is laced with childhood scars. He cackles. Maybe that’s how he got those marks, not from wriggling through a church’s fence and getting his neck snagged like everyone says. Maybe, one day, someone got sick and tired of him, and slashed his neck with knives. If only they’d managed to kill him.

Mama screams. Grabs the hem of my dress. “Nelah, please!”

Limbani is startled when tears crawl down my face.

“What? Didn’t you think I could cry? I never took your sister’s life away. Her body was given to me. Live with it.”

I walk out and never come back for any more of the family lunches my poor, sweet mother holds.

#

I am the Black Womb; everything I touch erodes.

Our last hope, our last resort, is Wombcubator specialist Dr. Nnete Senatla, an obstetrician-gynecologist and fertility researcher near Rasesa village at the Matsieng Fertility Fund, the site of water-well wombs that allegedly influence the Murder Trials .

We’re thirty minutes early at the forty-nine hectare heritage site, so we make our way to Matsieng’s creation grounds. Verdant lawns separate it from the Matsieng Fertility Fund. In the distance, koppies lull the land, whilst expansive blue skies are smeared with few cirrus clouds and too much sun. The path we take rises to become the green roof of the custodian’s brick-faced office, covering it with veld for the dry, arid climate. Opposite it is the paved food court where smoke rises from sizzling boerewors; vendor stalls fry magwinya, fries, noodles, and stews jam-packed with hot spices as a line of chattering people wait to purchase some bunny chows. We pass by a huddled group of sweaty varsity students who are bickering over their brochures in Seherero. Eli and I make our way done a narrow path lined with thorny trees that leads to the rocky outcropping sheltered by jackalberry trees. The rocks swirl across the site in strata of browns and reds, and punched into them are the deep groves of shapeless openings. Nearby stands a young man with a patted-down Afro, button-down shirt and corduroy pants tied high above his waist with a worn-out belt. He recites the history of the site whilst pointing to the deep crevices.

“This is where a colossal fearsome female God climbed out of this waterhole,” he says in a Sengwato dialect to a family of five Batswana, “bringing with Xem the first ancestors of our tribes, straight from the earth’s womb. This is why we refer to these as waterwombs.”

Eli leans back, hands deep in his pockets, listening with amusement.

I peer into the chasmic craters, but only darkness echoes back. Matsieng ascended from the amniotic underwater of earth’s womb, birthing our autochthonous tribes, guiding their passage as they clambered out of this crater, scarring the surface with their footprints. Most natives, though, believe that it was a large one-legged man and not a woman, whilst others concur that whatever crept from the craters was a non-binary God.

“There used to be only two waterholes, but over the years, more mysteriously appeared already impregnated by unknown phenomenon,” the guide continues. “People come from all over the word to collect this water, sometimes hued pink, like diluted blood, to sell and use for ritual purposes. The waters are very sacred and are essential to many rituals, blessing believers with miracles.”

“Sacred water, nè?” Eli muses. “So what has this water gotten you?” I nudge him because he’s staring at the guide in a judgmental way, as if to say, “If this water were so holy, why are you so poor, with a job like this?” Eli sometimes forgets that his privilege obstructs him from perceiving other people’s struggles.

“You’re one of the skeptics, nè?” the guide asks, staring at Eli with raised bushy eyebrows, flecked grey-white. “Terrible situations often turn people like you into believers. I do wish you well, but let’s hope you don’t meet that predicament.”

His warning sends a shiver trembling down my spine. Eli, however, seems unperturbed. The imprints embedded in the rocks are footprints of animals and people. But Eli wrinkles his nose at the petroglyphs. “Aren’t these cartoon sketches made by herdsmen of those times?” The family observes us with irritation; I’m burning in embarrassment.

“He’s referring to the other myths that dispute this creation folklore,” I say by way of apology.

The guide shakes his head, tutting. “Sometimes if you touch these marks, you can still feel powerful energy reverberate through this rock.”

“Maybe I should have a sip of that. I could become a billionaire, nè?” Eli whispers, clutching his belly as he chuckles.

I glance at him in reprimand. “Eish, be more respectful, will you? Besides, the administrators of the Murder Trials believe in this for some odd reason.”

Eli shakes his head, rolling his eyes. “Fucked up shit, I tell you.” He stops. “Why are you looking at me like that?”

“I’m now realizing why no one would ever take you to church.”

The guide raises his hands to an elderly man joining us, the sun glistening on the newcomer’s chiskop haircut. “The world of Matsieng’s era had neither death nor disease. After some time, Xe returned back to this waterwomb, cursing our vices with death and illness. Despite that, we are tied to this land and, regardless of how far we travel, this land is our ancestors’ dialect.”

“So this God-thing lies buried deep beneath the earth?” Eli asks with a smirk. “For how many millennia is that now?

Why must women—even powerful ones—always live out our existences buried? Why remain beneath the earth with all that power? Maybe Matsieng’s been restrained, or Xe’s waiting for something. I’m crazy if I believe in this.

I point further ahead to a secluded path leading to a curved roof supported by tusk-like columns, white as clean bone. “What’s there?”

The custodian cranes his neck. “The Murder Trials Section, but that’s for authorized access only.”

“Do the waterholes stretch back that far?” I ask.

He shrugs. “Can’t say.” He turns, walks away whistling. What do the Murder Trials have to do with the rest of the waterholes? Wisps of shadowy smoke rise above the tree line, and it sounds like voices. I shake myself out of my trance. Smoke has no voice. It’s only the chattering of the crowd of people surrounding us.

Eli tugs me by the shoulder and we walk back to the Matsieng Fertility Fund, a white-ash building clad in concrete that folds in and around its internal spaces like a shell. It reminds me of why I love architecture, the breath of the past held in the present. From the revolving doors, the specialist waves to us. She ushers us in through the spacious lobby, down wide reflective hallways and into a cavernous-like facility.

“My womb is a minefield,” I tell Nnete as we stand within the facility’s vast underground gestation space. “It blows up any existing fetus.”

Elifasi wraps his arm around me. “My wife is a cynic. We wanted to forego the artificial route, but that proved futile.”

Nnete gives a warm smile, full of understanding sadness. “Historically, women carried babies to term. That’s declined exponentially over the years. We curate an embryo using IVF and transplant the embryo into our Wombcubator, which is our term for artificial wombs.” Nnete points out the Wombcubators: minuscule oval spaceships hanging in deep-set alcoves in the walls, each accompanied by an intimate set of beechwood tables and armchairs upholstered in muted colors. Close to a hundred Wombcubators across all floor levels. They glow two colors: amber and blue. The former signals that something is wrong—perhaps a lack of nutrients or technological errors—to the observing doctors and scientists, whilst the latter indicates that the system is functioning perfectly. “The Wombcubator is AI- and human-monitored—nothing ever goes wrong. You’ll be able to monitor the fetus’s vitals and growth through visual feeds linked to your cellphones and other devices, which will allow you to see and talk to the baby remotely.”

She shows us around the facility, adding occasional explanations. “The fetus develops in a controlled Synthuterus environment. We emulate the climate of the womb through controlled dosages and nutrients.” She pauses at a station of triplets hovering in amber liquid within their Wombcubator, taps a series of instruction onto its screen and the liquid changes to blue. “Our technology can control the biological clock, speeding up cell activity to reduce the length of telomeres to that of a required age. Our technology accounts for bone therapy and brain development—all very extensive genetic manipulation. Our machinery will sequence your genomes to read and optimize your DNA, to eliminate diseases and disabilities. If you want to fully edit your child, to control how they look and what they like—”

“No,” I whisper, tracing my fingers on the cold glass. “I want them to be who they are, not what we want.”

“But, babe, we could have a genius,” Elifasi says.

“God gave you free will. Why must we take it away from another being just because we can?” I say. “That is too superficial.”

My husband rolls his eyes. “You need to get with the times. You can’t fuse science and religious dogma. We’re having an artificial birth—now you’re talking about God. We threw God out the window the minute we stepped into this facility.”

In the end, we sign over our entire savings account, a mortgage, and a loan. And twelve weeks later, there, our little baby floating in their Wombcubator. I convinced Eli to waive our right to choose the gender so we’ll be surprised by the reveal. And it’s a girl!

But I still feel the chill of Dr. Senatla’s warning: “The Wombcubator has a kill switch should anything go wrong with either the development of the baby, or late payments.” That’s all I can think about. I can’t lose another baby. “Failure to pay the charges and monthly medical bills means you lose ownership of your daughter, which will automatically give us the authorization to either terminate it or foster it for the Body Hope Facility’s supply chain, that’s if it can fit in their annual budget.”

My husband hugs me. “Life’s working out for us, isn’t it? The baby. Our perfect home. Our perfect family.”

In our bedroom, I extract a hologram feed from my watch that pulls up visuals from the Matsieng Fertility Fund. I stare at the subterranean Wombcubator pod. Beneath the flesh of the glass lies my little sweetheart’s heartbeat. It’s like ordering a meal, then fetching it once it’s fully cooked. A plaque below the pod glows, reading: 28 WEEKS REMAINING UNTIL I AM BORN. I trace the edges of the transparent hologram with my fingers and watch my hand bleed through the hologram’s projection.

Excerpt from Womb City by Tlotlo Tsamaase shared with the permission of Erewhon Books.

Womb City by Tlotlo Tsamaase will be released January 23, 2024.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about James Cameron’s Avatar: The Way of Water.