December 24, 2024

2 min read

Wikipedia Searches Reveal Differing Styles of Curiosity

Are you a “hunter” or a “busybody”?

The website Wikipedia describes curiosity as a “quality related to inquisitive thinking, such as exploration, investigation, and learning, evident in humans and other animals.” But there is a lot more to this prime motivator for so much of human behavior—and Wikipedia, as the world’s largest encyclopedia, is now helping social scientists deepen the definition of curiosity.

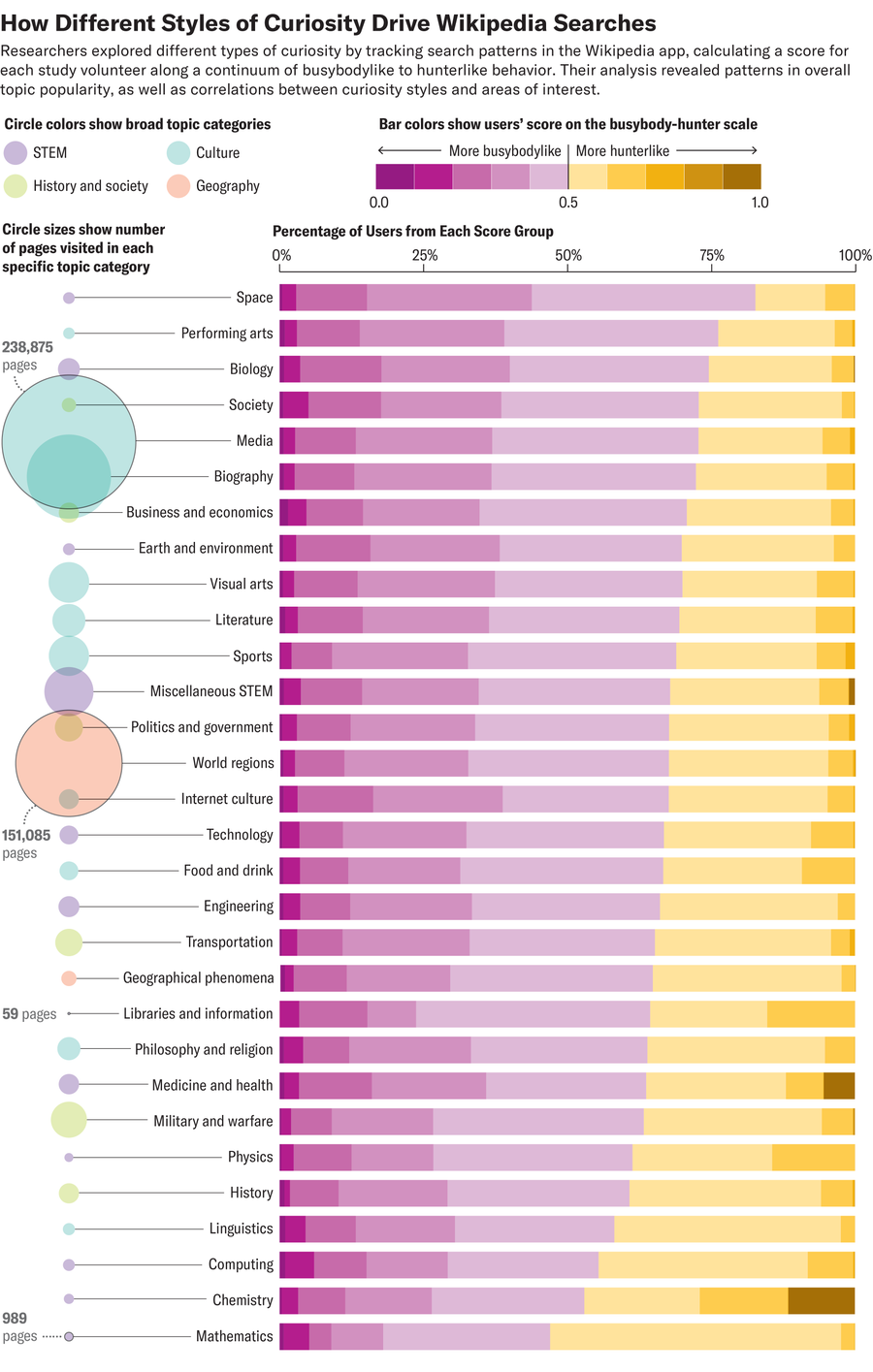

Tracing how Wikipedia searchers flit among topics and lose themselves in Wiki rabbit holes revealed three different styles of human inquisitiveness: the “busybody,” the “hunter” and the “dancer.”

“Curiosity actually works by connecting pieces of information, not just acquiring them.” —Dani Bassett, University of Pennsylvania

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In this lexicon, a busybody traces a zigzagging route through many often distantly related topics. A hunter, in contrast, searches with sustained focus, moving among a relatively small number of closely related articles. A dancer links together highly disparate topics to try to synthesize new ideas. “Curiosity actually works by connecting pieces of information, not just acquiring them,” says University of Pennsylvania network scientist Dani Bassett, cosenior author on a recent study of these curiosity types in Science Advances. “It’s not as if we go through the world and pick up a piece of information and put it in our pockets like a stone. Instead we gather information and connect it to stuff that we already know.”

The team tracked more than 482,000 people using Wikipedia’s mobile app in 50 countries or territories and 14 languages. The researchers charted these users’ paths using “knowledge networks” of connected information, which depict how closely one search topic (a node in the network) is related to another. Beyond just mapping the connections, they linked curiosity styles to location-based indicators of well-being, inequality, and other measures.

In countries with higher education levels and greater gender equality, people browsed more like busybodies. In countries with lower scores on these variables, people browsed like hunters. Bassett hypothesizes that “in countries that have more structures of oppression or patriarchal forces, there may be a constraining of knowledge production that pushes people more toward this hyperfocus.” The researchers also analyzed topics of interest, ranging from physics to visual arts, for busybodies compared with hunters (graphic). Dancer patterns, more recently confirmed, were excluded.

Princeton University psychologist Erik Nook praised the study’s “dazzlingly large” scope. The authors, he says, brought together expertise from a range of fields—topology, psychology, cognitive science, affective science, clinical science, sociology and computational modeling—to reveal a “host of insights into human behavior.”

The seeds of this work were planted in 2016 when Bassett and their twin brother, Perry Zurn, a professor of philosophy at American University, noticed that plenty of academic research had examined creativity—but relatively little had gone to its requisite precursor, curiosity. Zurn emerged from a deep dive into 2,000 years of Western historical and philosophical literature with descriptions of various curiosity styles, including the three investigated in the recent paper. Wikipedia then provided the real-world test bed to confirm this busybody-hunter-dancer typology, drawn from the work of philosophical greats. Heidegger and Nietzsche could never have imagined that their work would one day influence the network science of Wiki rabbit holes.