This story is a collaboration between CBC News and the Investigative Journalism Foundation (IJF).

Read this story in Punjabi. / ਇਸ ਖ਼ਬਰ ਨੂੰ ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਵਿਚ ਪੜ੍ਹੋ

Read this story in Tagalog. / Basahin ang artikulo na ito sa Tagalog.

It took less than five minutes on the phone for a man selling a job on Kijiji to name his price: $25,000.

Our undercover reporter, posing as a recently graduated international student eager for work and permanent residency (PR) in Canada, had replied to the seller’s classified ad for a government-approved position in food service.

During that July phone call, the man asked her if she needed “the job with LMIA or just LMIA without job.”

The LMIA, or Labour Market Impact Assessment, the man was selling is a document issued to employers by the federal government. It allows them to hire foreign workers after employers prove they can’t find a Canadian or a permanent resident to fill a position.

These LMIA-supported positions not only allow foreign nationals to work legally in Canada but also increase their chances of becoming permanent residents. Given the federal government’s announcement on Thursday that it would shrink the number of available PR spots starting next year, these permits could become even more coveted.

Under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, charging foreign workers any money for LMIAs is illegal.

Investigative Journalism Foundation reporter Apurva Bhat covertly contacted several online advertisers selling job offers to immigrants for cash. In one call, the seller tells her she could get a job offer for a role that doesn’t exist — but only if she pays $25,000.

“That’s outright fraud,” said Ravi Jain, principal lawyer of Jain Immigration Law in Toronto.

“This person is doing something very illegal and they’re doing it quite openly,” said Jain, after listening to our recorded calls with prospective sellers, including the one on Kijiji. “It’s sad that there are people who know enough about the system that they’re willing to exploit it.”

This particular seller is one of dozens tracked by our team who continued to advertise these positions for cash to immigrants on Facebook Marketplace and Kijiji, even after Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) announced new measures in August to “weed out misuse and fraud” in the temporary foreign worker program.

In a months-long investigation, CBC and its reporting partner the Investigative Journalism Foundation (IJF) contacted several of these online sellers. We found these immigration schemes come with a choice of a “real” position or a “fake” one — complete with supporting documentation, such as fraudulent pay stubs and tax slips to submit to federal authorities as evidence of Canadian work experience.

Deals include ’employer cost’

In two exchanges with sellers, our reporter disclosed she did not have any relevant work experience for specific skilled LMIA positions. She was still pitched LMIA-approved job offers for prices between $25,000 to $45,000.

In another exchange, the seller explained how our reporter could pay to be added to an employer’s payroll, after clarifying there was no actual work available.

“Clearly they’re complicit,” said Jain. “This employer is likely getting a very large payout.”

We discovered some of these deals explicitly included an “employer cost” upwards of $27,000 — even though employers are prohibited from charging foreign nationals any recruitment fees.

Yet another seller told our reporter that even though there was no real job, the initial fee would include $3,000 for the position to be posted on job boards “to show that we have done our best to hire from the existing [pool], but we [didn’t] find anyone who is a permanent resident [or] a Canadian citizen” — a requirement for employers before getting an LMIA.

These deals contravene the stated purpose of LMIAs, which the federal government introduced in 2014 as “a last and limited resort to fill acute labour shortages on a temporary basis when qualified Canadians are not available.”

Historically, a higher proportion of workers in farms, greenhouses and fish and seafood plants have been hired through LMIAs.

Multiple immigration lawyers consulted by CBC/IJF say that both temporary foreign workers who pay for these deals and individuals who sell them could be charged with misrepresentation or counselling misrepresentation, violating Canadian immigration law. If found guilty, offenders can face fines of up to $100,000 and up to five years in jail.

Immigration experts say many foreign workers may not know these deals are illegal. But as Jain points out, migrants pay the highest price for participating in them — both financially and because they are complicit in a crime. If they report these schemes, they risk deportation and a five-year ban from entering Canada.

Two online sellers who made detailed offers to our undercover reporter in July were contacted by CBC/IJF for subsequent comment. They did not respond to multiple requests.

Ads triple after Ottawa intervenes

Between July and September, our investigative team documented more than 125 online ads advertising LMIA work permits or LMIA-approved jobs in 17 Canadian cities by individuals presenting themselves as sellers, recruitment agencies or regulated immigration consultants.

We found the volume of online ads offering LMIA positions for cash has dramatically increased in the weeks following several government changes to limit access to the valuable permits. In July, CBC documented 29 ads circulating online; by September, that number had more than tripled to 97.

Almost a quarter of the ads were geolocated in the predominantly immigrant community of Brampton, Ont.

In late August, ESDC announced it would reduce the number of temporary foreign workers in Canada by refusing to process LMIAs in major cities with high unemployment except in industries experiencing labour shortages, such as health care and construction.

But these same industries were promoted in the ads catalogued by CBC/IJF in September. For example, one ad posted on Sept. 4 promotes positions in “construction and hospitality,” followed by a line in Hindi stating the LMIA could be obtained “with and without work.”

When our undercover reporter contacted online sellers in September, she was still given opportunities to buy LMIA-approved job offers costing up to $40,000 within minutes.

However, prospective sellers were more tight-lipped, declining to discuss details of the arrangement over the phone or to send anything in writing. Instead, our reporter was encouraged to come to their office in the Greater Toronto Area, cash in hand.

One seller refused to provide specific details of the proposed scheme in writing.

“If I don’t trust you, how can I tell you?” he told our undercover reporter. “There are so many things going on in the market … it can go against me.”

On Oct. 21, ESDC announced it would enhance data sharing by working with provinces, territories and employer registries “to ensure that only genuine and legitimate job offers are approved, helping prevent misuse of the program and ensuring stronger worker protection.”

In a statement to CBC/IJF, Employment and Social Development Canada stressed that “regulatory changes are currently in the process of being implemented,” and that in the future, the department will take more time to “investigate and assess all applications.”

It added that it “works closely with all departments to find and hold the culprit accountable” when illegal scams are reported.

The department did not answer CBC/IJF’s questions regarding how many agents it employs to investigate LMIA schemes, nor how many investigations it has launched against employers or companies in the past five years.

Pressure for PR

Foreign nationals hired to work LMIA positions gain an additional 50 points on their Comprehensive Ranking System score, a points-based system used to assess candidates for permanent residency.

Because of this, Calgary-based regulated immigration consultant Steven Paolasini says these LMIA positions, and the extra points they come with, have become highly coveted by millions of foreign nationals competing for the limited spots in the PR race.

On Thursday, the federal government further reduced the total number of permanent residents it would admit in 2025 from 500,000 to 395,000, with more cuts in later years, creating added pressure on temporary foreign residents vying for those spots.

“People can [have] the same [score] on language, the same on education, the same on Canadian experience. What’s going to set them apart now is that 50 points of arranged employment or potentially 200 for a senior manager LMIA,” Paolasini explained.

According to Statistics Canada, the number of international students, temporary foreign workers and asylum seekers has climbed from 1.3 million in 2021 to nearly 2.8 million in the second quarter of this year.

“So what happens to the 2.8 million people?” said Jain.

“That pie is simply not big enough.… That’s where the pressure comes to get extra points for a permanent residence. [So foreign nationals] go to unscrupulous people who are selling LMIAs.”

A ‘failure of policy’ in designing the immigration system has resulted in a situation where many international students are now desperate for permanent residency, says Ravi Jain, principal lawyer of Jain Immigration Law in Toronto. International education accounts for more than $22 billion in economic activity every year in Canada.

LMIA program ‘exploitative at its core’

Several experts told CBC/IJF that tinkering wouldn’t solve the fundamental problem with Canada’s LMIA system.

John No, a labour lawyer and interim clinic director of Parkdale Community Legal Services in Toronto, says that’s because the program is “exploitative at its core.”

“It’s essentially indentured servitude,” he said.

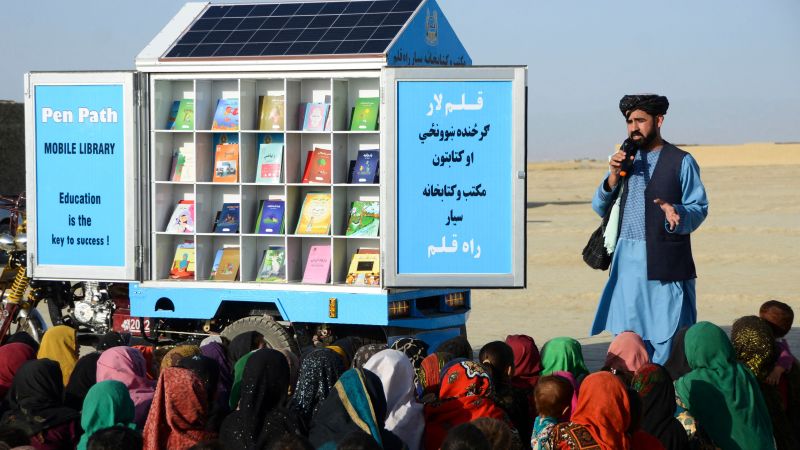

Canada’s temporary foreign worker program, through which LMIAs are issued, was similarly called a “breeding ground for contemporary forms of slavery” by UN special rapporteur Tomoya Obokata, who published a report in August following his visit to Canada in 2023.

Because an LMIA ties a worker to a specific employer, foreign nationals end up becoming “stuck,” No said.

As a result, wages are suppressed and workers have no freedom of movement between employers, says No.

“It is creating … two categories of people. There [are] people who have the freedom to shop around for good working conditions and there [are] people who are not allowed to.”

As Canada tightens its path to permanent residency, more immigration schemes are appearing online, offering fake jobs to foreign workers in exchange for up to $45,000.